Science / Tech

The Life and Death of a Medical Study

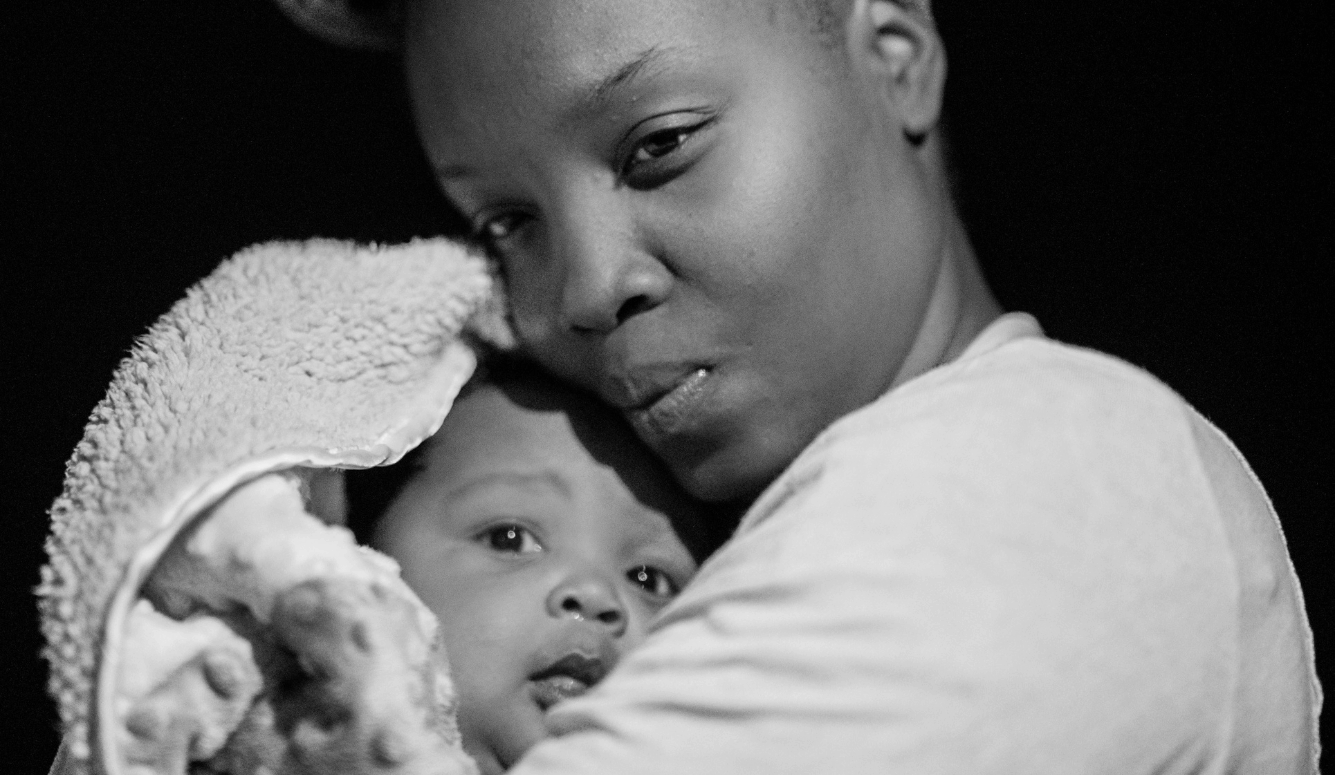

A 2015 study found that black newborns attended by white doctors die at twice the rate of those in the care of black doctors. The study’s refutation last year has not altered the progressive narrative of systemic racism in medicine.

What happens after an influential medical study is refuted? Perhaps not much. In one revealing case, a study published in 2020 has been cited over 700 times, while its refutation has been cited exactly once over the four months since its open-access publication in the same major journal—an imbalance so grotesque that it mocks the conception of science as a self-correcting enterprise.

Based on a review of records of 1.8 million births in Florida hospitals from 1992 to 2015, the original study by Greenwood et al. found that black newborns attended by white doctors died at twice the rate of those in the care of black doctors—a result that appeared to confirm the progressive portrayal of medicine as a racist institution. Never before, perhaps, had the importance of racial concordance in clinical medicine been demonstrated so dramatically. The invalidation of the Greenwood finding four years later has gone all but unnoticed and has had no effect on the progressive narrative.

I first learned of the Greenwood study from an editorial deploring “systemic racism” in urology without offering a single example of the biased practice of medicine in that discipline. The authors write:

Studies have shown the more insidious effects of racial discrimination, such as chronically high cortisol levels in individuals experiencing weekly discrimination and, conversely, reductions in diabetes and major depression rates when Black individuals move to more affluent and safer neighborhoods. If these examples are not alarming enough, Greenwood and colleagues showed that Black infants have threefold higher mortality when cared for by a white physician than those cared for by a Black physician.